The nexus of my six honeycomb pieces began with my body- with a metamorphosis that happened at some point last year that fundamentally changed the way I exist in the world. I cannot say for sure when it began, only that it began slowly and so quietly that I did not notice the change at first—the tingling sensation in my legs at night as I try to fall asleep, until the tingling took hold, and caught fire. Of course I was worried, but I pushed the worry away, and continued living my life: getting up at 4 am so I could be to the gym by five for a high-intensity interval training session I tried to do every single day. Yet, little by little the pain found me there, too, and even though I would not admit it to myself that something might be wrong, I kept pushing myself until the pain sent me sprinting to the bathroom where, doubled over as wave after wave leveled me closer to the tile floor, I would try to wait out the raging storm as everything, everything emptied itself from me.

Physical things became a struggle to complete— for over a year, I struggled to run, to bike, to row, to lift weights, to stand for hours at work. I had to keep going because, I thought How else could I have any value in the world? I wondered if these symptoms indicated that I was lazy or so far out of shape that I had to work harder, and so I continued to push until just couldn’t anymore.

The road to finding a diagnosis was long, and suffice to say it is its own kind of essay—but another year of appointments with specialists, a year of blood tests and scans and imaging of me standing up, of me laying down, of me from the front, side back, me from the inside out finally revealed an injury I have carried my entire life but only recently felt: a chronic stress fracture in my spine. The fracture introduces an instability that, when I push too hard or stand too long, causes my bones to crush nerves that send wild electrical signals to the left side of my body. It is a debilitating, painful condition, and for which there is no surgical procedure, treatment or remedy— in other words, for which there is no cure. In the words of the surgeon, “It is only pain, Rebecca. You can live with that.”

The Honeycomb Project found me around this time the the news that I would never run another marathon again, never hike another mountain or never pedal the 560-some odd miles across the state of Nevada to the Utah border on my road bike like I wanted. What the future holds for me is a mystery. Perhaps it always has been that way—who knows, definitively, what awaits them in the days, months, and years to come? What I know: I have been an athlete my entire life, and that is how I moved through the world. The project invited me to consider, in a real and tangible way, six small answers to the fundamental question of: who am I now? What I can I see from this vantage point?

The six-point shape of the hexagon canvases intrigued me, as did the challenge of articulating a love of a place not with words—but through the language of the visual arts. I thought of a time during the Pandemic when I had a small life coaching practice focused on helping artists and writers find their purpose and direction within specific projects they were working on when they felt they had lost their way. The research of Maori psychotherapist David Grove informed some of the techniques I employed then, and with the uniquely shaped wooden canvases, those ideas returned to me now—perhaps I, too, needed to find a new way.

Like many, I had read anthropologist David Wade’s enthralling accounts of Polynesian seafaring cultures in The Wayfinders, and perhaps that is what led me to Grove, whose theories found their roots in Maori mythologies. These ancient peoples used acute perception to find their way, marking the current of the ocean and the cadence of the waves beneath their vessel, the orientation of the stars, the wind speed and direction among many other subtle, delicate points of data. Accounts like these suggest people can, in fact, find their way, if only we look hard enough and now how to see the world around us. “The sheer courage that true exploration implies [is] the brilliance of human adaptation,” writes Wade. This does not come without a cost, however. As author Philip Harland, writes “The Polynesians used to say you could tell a way finder by his bloodshot eyes.”

And so it comes down to something simple, something we—and certainly I—have somehow forgotten. It is a matter of looking— not a passive glance, not looking in the way that we do from day to day, but looking as though the eyes have fingers and can feel the bark of the tree, the grain of the sand, can smell the moist sage rising from the basin floor after a sudden rain. It is the direction from which the wind comes and goes, the speed and strength and temperature of that wind— does it gust? Is it sustained?

As I write these questions, I cannot help but wonder: truthfully, how often do we notice these things? How often, in my busy life with all those verbs running, cycling, swimming, rowing, going, going, going—have I?

These writers argue that to notice the world in this way is deeply human— and yet, it is somehow a skill that we have largely forgotten in our contemporary moment. The Honeycomb project seemed like an invitation to return to a part of myself that was older and more essential than my identity as an athlete. A part of me that knew how to find its way. With six canvases to complete (they are sold in a six pack on Amazon), and each canvas itself had six points. There seemed to be something serendipitous about it. Six, after all, is a special number, one that mathematicians and other thinkers have taken particular note of. Harland notes:

Six is a rule of thumb governing the number of data points necessary for information to reach a critical mass. It has been shown to be pervasive throughout nature, problem solving and social interaction…. Mathematically, six is the pivot of its divisors, which add and multiply exactly to the number itself: 1 + 2+ 3 = 6 = 1 x 2 x 3 (81).

Six is pervasive in nature. Not only do bees construct six-sided honeycomb, but snow (when it falls) forms a six-point crystalline structure in each individual snowflake. But, more importantly, it takes six coordinates in space to form a dynamic system of relationships around any given point—an idea proposed and refined by David Grove, and that he adapted into a therapeutic method of inquiry to assist clients with the intellectual, emotional and mental way finding we all need from time to time.

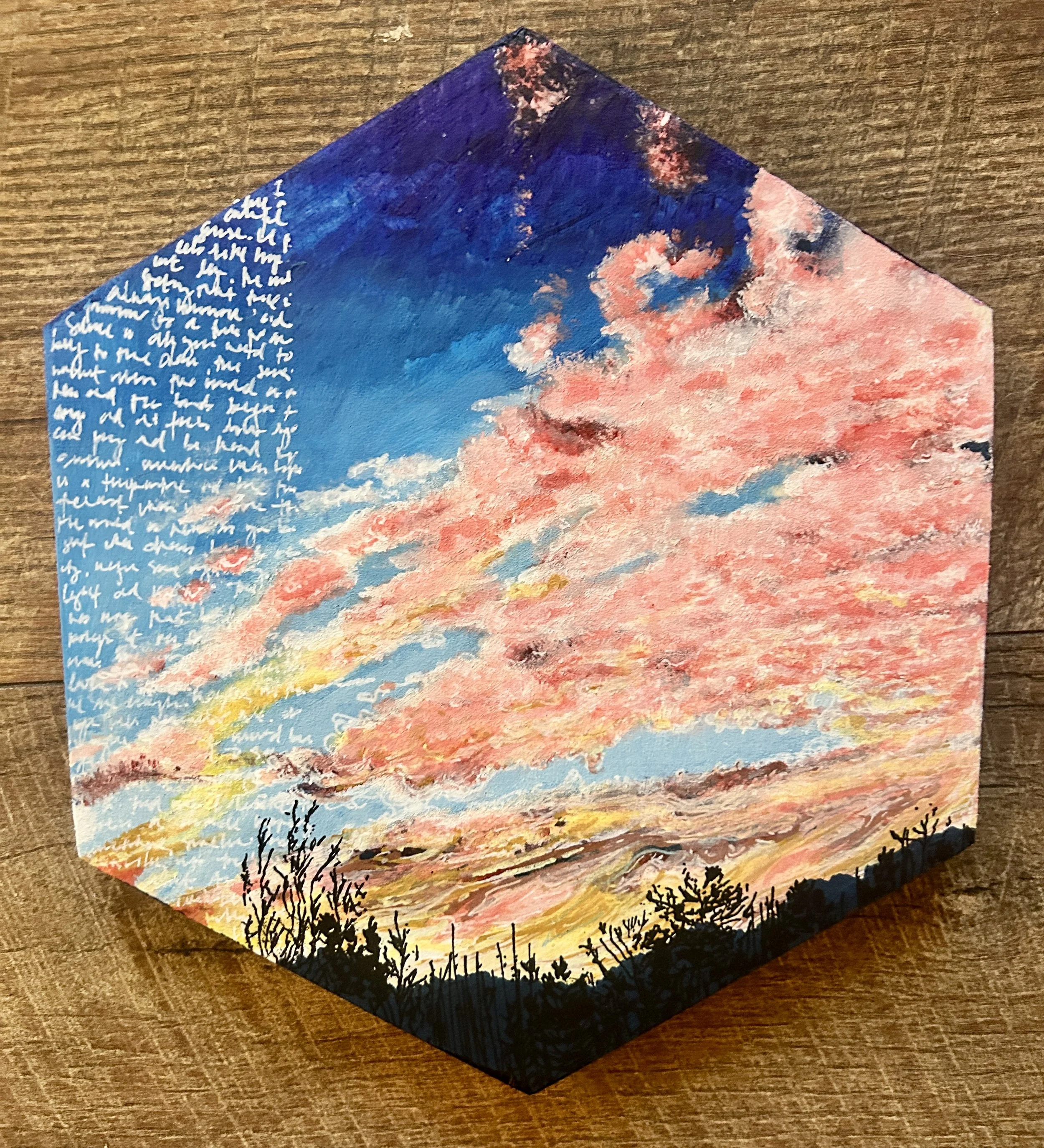

So, I decided to use my six hexagon-shaped canvases as a way finding tool for myself. To observe the world with close attention, to find and notice the salient details, here, to see what they could tell me about this new existence I have come to inhabit. These pieces represent the personal way finding of moving forward in world without running marathons, without bike races, without the linearity—the certainty—of a start and finish line. The hexagons are not linear nor do they progress in any real way from one to the other. They are glimpses of the places—moments—I have seen, even with my limited mobility.

The locations are not exotic or even iconic: an aspen grove down the Thomas Creek watershed not far from the grocery store where I shop; a lone cottonwood tree bare of leaves in winter a mile from my house on the banks of a dry watershed; the Carson River beneath the crepuscular winter light of dawn and a feather, there, discarded by a Stellar Jay; a sunrise I watched from my front yard on Christmas morning and a mysterious owl that comes to roost atop the eave of my garage at night. I have never seen him, but the evidence of his voice is undeniable, calling into the night, as if he, too, were asking some essential question.

Through six hexagon-shaped canvases, I was invited to return to my past: my grandmother, a visual artist, worked in oil on canvas. Although she passed away when I was very young, I felt her presence guide me through the techniques I have not practiced since my last formal art class freshman year in college. Back then, I was often frustrated with my clumsy hand, and my inability to make anything meaningful. This time—nearly twenty years later—it was not about creating anything perfect, not about pleasing others, and certainly not about “winning” anything— creating these canvases gently invited me to return from my forays into what was and what might be, and to exist solidly in the present. To exist as I am now, and to simply be. In so doing I found something unexpected: I found myself.

The Maori believed that no journey was impossible; it was only a matter of navigation. Perhaps it is a matter, also of not only finding the way, but finding a way, a method by which the journey can be undertaken. Six small steps, six small glimpses, six small incantations or prayers written across the wide sky upon which an image takes shape. In The Power of Six, Harland relates an old Maori myth at the beginning of his work inspired by the life and insights of David Grove, evoking the deeply rooted power of moving through the world—physically, mentally, emotionally, and spiritually—in this way.

“When a baby is born, six red stones are taken from the mother and placed into the earth in a sacred place. Those stones join the six of the last generation, the six that went before, and all the others put there through time” (7). The irony of this journey is that I expected to end up in a new place, when in fact my way finding using six hexagon-shaped canvases led me somewhere else. I connected to Nevada, my roots, to my family, and an artistic legacy I did not believe I was a part of—to my grandmother whose work was inspired by the natural landscape of high desert and mountainscape of the Sierra Nevada. Quite simply, the Honeycomb Project led me home.

Works Cited

Harland, Philip. The Power of Six a Six Part Guide to Self Knowledge. Wayfinder Press: London, 2009.

Wade, Davis. The Wayfinders: Ancient Wisdom Matters in the Modern World. House of Anansi Press: 2009.