Then, we are eight miles and one climb left and I see her.

We pass the woman I have been fighting this entire day.

She's at the base of Norris Canyon with another male rider covered in the white relics of salt sweat. We pass the quickly, and I don't look back to see if they hung on.

We hold a steady pace up Norris, and when I turn around, I hope not to see anyone behind our trio, I see my competition. I try to turn my depression and doubt around, and stand up, out of the saddle. She responds and sprints ahead of me, up the hill. A part of me knows that I have it in me to keep up, but the race doesn't end at the top of this hill, but is still another six miles away. This makes me pause, and settle into a pace which puts me between the girl and her partner, and Rich, who is behind me. I've given up, I think. I've failed.

The young guy who joined us could have ridden with the other two, and perhaps have finished faster. Instead, though, he lingers at the top of the hill to wait for Rich and I.

We're a team for the last part of the race, and I reel him back into our group of three.

When Rich takes the lead, we do at least 30 mph down that hill, me behind Rich and our new teammate behind me. We watch as my competition sails through the first green light, and it changes right behind her. We tap our shoes on the pavement impatiently (or, I do. The men are both track standing.) We hop into motion the second it turns green for us again.

And again, we move in pace line behind Rich, doing something like 30 mph. Again, we gain ground. Again, she and her partner sail through an intersection. And again, the light turns red for us.

When the light turns green, we again ride hard. Across an overpass, a right turn: we're mere blocks from the finish. I see the hotel on the right. We pass the driveway the girl and her partner took; I trust that Rich knows what he's doing. He leads me to the exit, much closer to the door through which the registration table resides. I unclip from my pedals, and dismount into a run, triathlon-style, for the registration table.

I don't think about the ethical implications of what I'm doing-- running in a cycling race is like baking sweets for a professor in order to pass hard final exam. I just do what I do: I hand of my bike to a friend who happens to be there, and I start running in cycling shoes, through the open door and down a hotel hallway as if this was, somehow a natural and normal thing to do.

Can I or can't I?-- these aren't my thoughts in the moment. It's as though I'm not 34 years anymore, but 4; I want to win! Improbable and unearned as it is. I'm presented with it after 15 hours of believing I'm a washed-up old nobody: here it is. A chance for second-best to say that all the 4am early mornings, all the missed afternoons with my family, all the sores and scabs, and the feeling like I could fall asleep at the wheel during my two-hour daily commute and all the times I didn't write, but rode-- all of that somehow amounted to something tangible. My life, somehow, for a second, could have meaning.

"Number 51" I tell the man behind the registration table, and the moment ends.

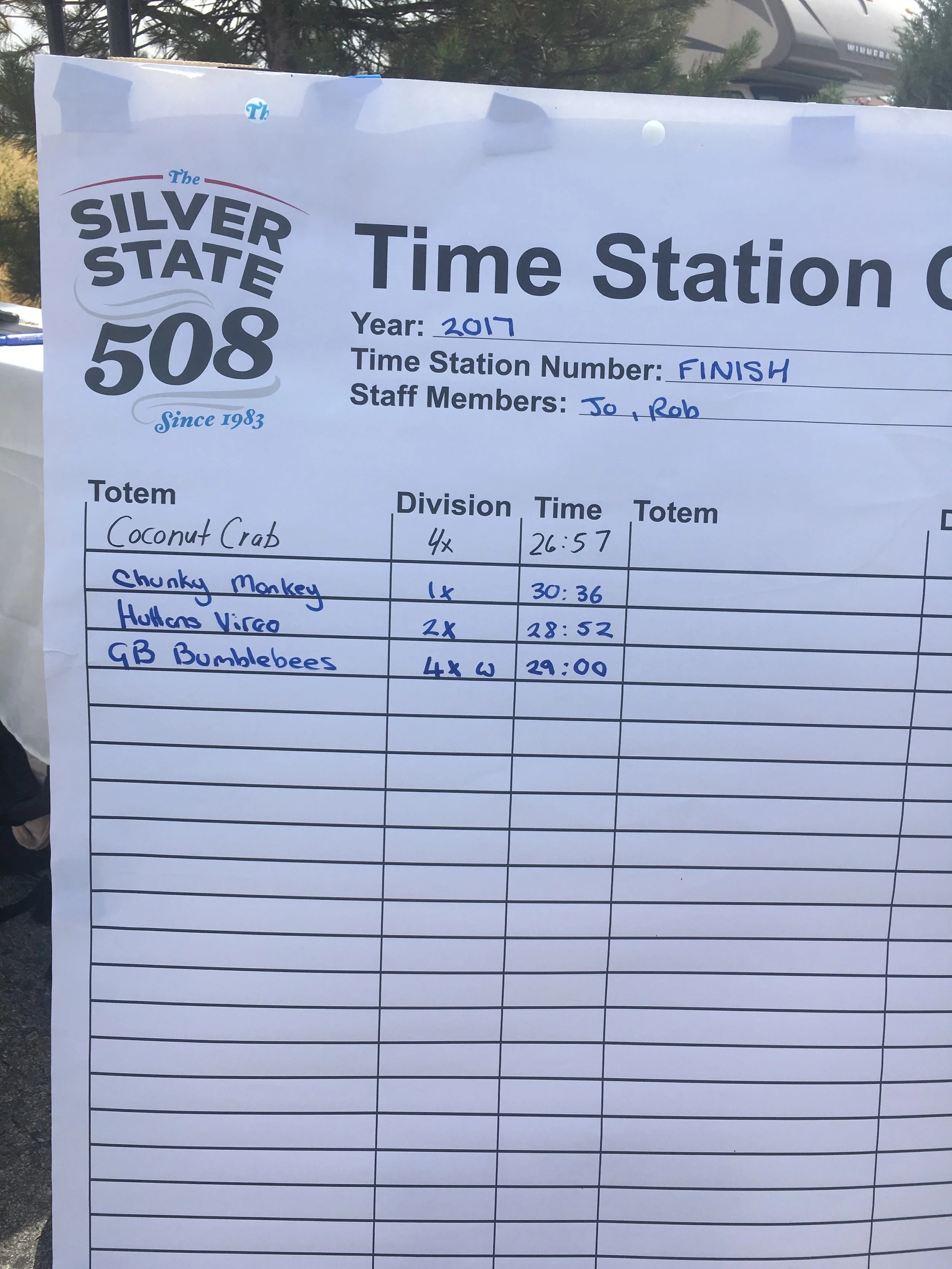

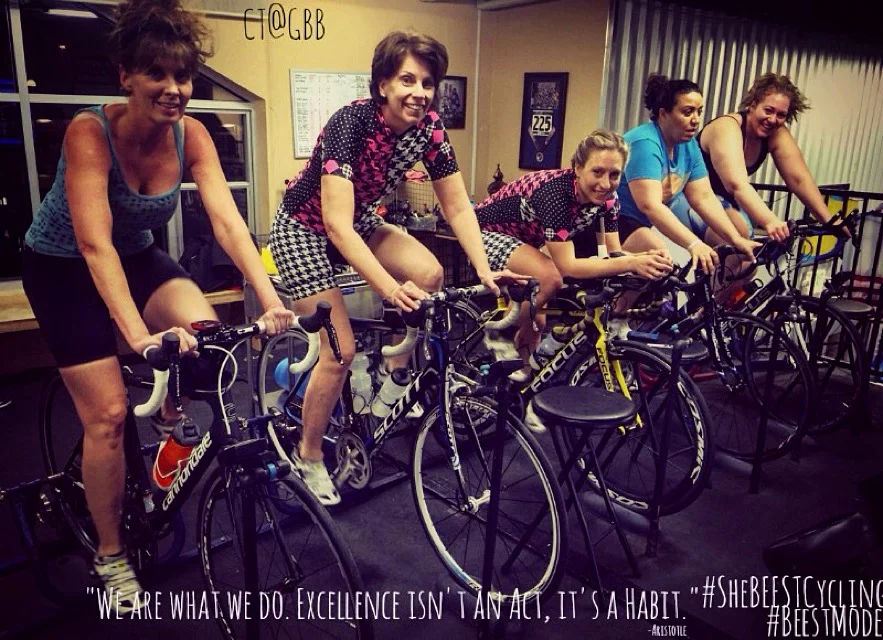

I turn around, and there is my competition: this strong, able-bodied woman who has trained and sacrificed just as I have. We congratulate each other before I leave the room to find Rich and my bumblebee bike.

No matter what I may think or how old I feel, this will continue in two weeks. I hope, by then, I learn not to feel my age, but embrace it as another measure of time-- a measure against we all race.