Disclaimer.

Our team "portrait" taken the night before the race. From left to right: Rhonda Yeager (stage 1 and stage 5), Rebecca Eckland (stage 4 and stage 8), Katie Heyder (stage 3 and stage 7) and Monica Grashius (stage 2 and stage 6.) Photo credit: Chris Kostman

I've been thinking about the nature of nonfiction a lot lately, mainly because I have several writing projects on my plate, but also because I spent the better part of my twenties studying-- and writing-- in that particular genre. So, in a way, it's become my modus operandi for how I organize my thoughts, even without realizing it. I’ve also been thinking a lot about cycling and how that fits into my writing life (most times, it doesn’t.) Races like the 508, though, which require so much explaining and storytelling to give anyone a sense of its breadth— allow the two worlds to collide.

For me, writing nonfiction is a lot like taking a photograph: you have to frame your subject while taking into consideration what exists in the natural world around it. It's an act of selection--of focus. If you take a picture of the road, you might miss the mountain range to the right, or the clouds directly above you. If you photograph the tree, you miss the river, (etc.) Events, therefore, are also snapshots of the end of a particular journey— of the training it took to compete, yes. But, also of whatever other challenges circle through my ligaments and mind, and what little I’m left with is what I tend to write.

These days, photographs are not necessarily true; they render something that looks true enough. This is not that kind of photograph. This race report takes neither the high or the low road— instead, it focuses on the truest moments across 508 miles shared by six unlikely athletes brought together by a common purpose: to break a few barriers and to set a record for the “toughest 48 hours in sport.”

Start & Stage 1.

It's 6:45 am on Friday, September 15th. The sunrise has a light pinkish hue to it; the air bites at the skin with its teeth. There are a handful of cyclists gathered in front of the Hilton Garden Inn, a hotel in Reno's South Meadows. For the "toughest 48-hours in sport" you'd think there would be more fanfare: more spectators, more families… just more. But, ultra-endurance sports are not social: they are individual struggles, spread out across roads and mountains. The lucky thing— for a team, anyway— is that you get to share these private moments with a handful of other people.

All of us a the start line the crisp morning of the race. Left to right: Monica, Rhonda (ready to race!), Rebecca and Katie.

Our team’s first rider, Rhonda Y., is a true Reno local and resident and also an accomplished cyclist. A Cat 2 racer, she earned her USAC status through years of hard work, racing, training and talent. In 2011, she was struck by Hummer, and injured so badly that she had roads and screws (a level 5 fusion) placed in her back. Yet, she returned to racing and won several USAC Crit races, working her way to her current Cat 2 status. Two years ago, she married and had a little boy, Till, who is 1 1/2 years old.

As she stood at the start line, another racer told her: "I'm a very fast climber.”

The starting line, where things started to get "weird" right away. Rhonda, in the black, red and white Audi kit is in the center of the frame. Great Basin Ichthyosaur's rider, Jami Horner, is in the blue Great Basin kit to her left.

When the race began, she sat back and watched the two "leaders" (including the “very fast climber”) struggle up Geiger Grade. Rhonda picked her moment, and attacked. "I got to Geiger Summit alone. I looked back and there was no one there," she said.

Into Virginia City and down Six Mile Canyon, other riders didn't stop at the stop signs despite race rules which dictate otherwise. She watched other riders break the rules and accelerate down the narrow road. Yet, Rhonda would emerge as the third rider to meet NV Hwy 50. Strong headwinds and construction made for an interesting first exchange point as teammates Monica and Katie organized the mini-bus (the shaggin’ wagon, as my partner, Rich— who was competing on another team— called it.) I sat up front with our driver, Linda, an ultra-endurance athlete recovering from her own traffic accident, trying to settle into the cadence of the race.

Already, we had a rivalry, and it wasn’t with the other Reno team like I had expected. Each and every woman in that mini bus had their sights set no on the only team to wear skin suits for the first two legs of the race. The one with the fast climber. As our second rider embarked on the 31.5 mile stage to Fallon, I knew this year was different from the previous three I had raced. This race was gut-deep.

Flat and Fast Stage 2.

The Silver State 508 is a non-stop 508-mile time trial race that has five different racing categories: solo- randonneur, solo, 2-person relay and 4-person relay. Because people come in two flavors (male and female) and bikes come in five (standard, recumbent, classic, fixed gear and tandem) the permutation of race categories is more than I want to calculate (hey, I became a writer for a reason.)

Monica, riding along highway 50 for her "flat and fast" stage 2 makes it look effortless. Really fun to watch, Monica inspired us all to keep our game faces on.

Mini-orange bus fun early in the race as Monica kicks ass!

Never before in the history of the Silver State 508 has a four-woman team even toed the line. There were four-woman teams in the Furnace Creek 508, but they never cracked the top-ten. I never imagined that, in gathering local female racers, that we would be competitive with male teams. I only wanted us to finish, to have a good time and to get to know each other better.

But, maybe that reveals some deeper bias about what men and women are capable of. Or, of what we are willing to accept from a person depending on their gender, their socio-economic status, the color of their skin or the cost of the bike upon which they log their miles.

Monica G., our second rider, is probably the woman who articulates this the best. Tall, athletic and the most determined (tenacious) person I know, she’s also very wise. In the weeks prior to the race, I internet-stalked all my teammates, cobbling together a sponsor letter to convince some local business to loan us a vehicle for the race. I found a quote she’d offered to an athletic trainer who had helped her prepare for Leadville last year. She wrote: “Life is full of labels and definitions. It’s not number; a weight, finish time, salary, age, heart rate, speed, watts or even tire size. It’s not a title or degree. It’s not a membership to a country club. It’s not finishing one race, it’s finishing each day with grace and humility. It’s the opportunity to show up at the start line.”

Katie (left) grabs the GPS tracker from Monica (right) at the exchange point in Harmon Junction at the East side of Fallon.

Monica showed up for this stage. She rode so strong that our crew, Linda, remarked: “I hate to say it, but she rides like a guy. And if anyone ever says that to me, I’m going to think of Monica, and I’m going to take it as a compliment. Man, she’s strong.”

We got to the exchange point well ahead of our companion Great Basin (Reno) team. The skin-suit team was still in front of us, though. Our third rider, Katie, got on her Q-Roo TT bike with a fire in her eyes that she would do the best she could for the next 106 miles.

Long, cold and windy. Stage 3.

The Silver State 508 is a long enough race that you have to think about logistics and details. And, not to throw myself under our mini-bus—which I somehow managed to secure by coordinating with Rich who owns Great Basin Bicycles and Darrell Plumber of Sierra Nevada Properties— I will freely admit that “logistics and details” are not really my thing. As a literary artist, I am a more conceptual and abstract thinker: put me in charge of the Facebook and twitter feed and watch me literally blow it up. Things like a vehicle, coolers for food and water and ice, etc. That’s definitely not my thing. (We have a saying in my household: I can fix it if it’s a manuscript. If not, you’re on your own.)

So, if it were up to me, we might subsist on dry turkey sandwiches, which is what I did, because somehow all the food I packed disappeared and I couldn’t locate any of it throughout the duration of the race. (I would later discover it ended up on the Great Basin Ichthyosaur Van— our companion team. Oh well. ) Luckily, my teammates were all a lot more organized than I was. Katie, for instance, stocked the van with three coolers, one of which held ice water that we didn’t go through quite as quickly as we feared (it was colder this year than in the past) but that proved invaluable.

Katie, with her Q-Roo TT bike, rode the flats and downhills at mach one speed, pulling us across the Nevada’s vast Great Basin on hwy. 50. Past the dunes of Sand Mountain, the bombing range of Dixie Valley and Middlegate— a bar/motel/semi-landmark along the route. Here is where we’d pull the bus off the road to stop and wait for our rider to pass.

Team shot with the orange bus graciously donated by Sierra Nevada Properties. Katie (not pictured) is riding the 106-mile third stage of the race. Left to right: Rhonda Y., Rebecca E. and crew Linda.

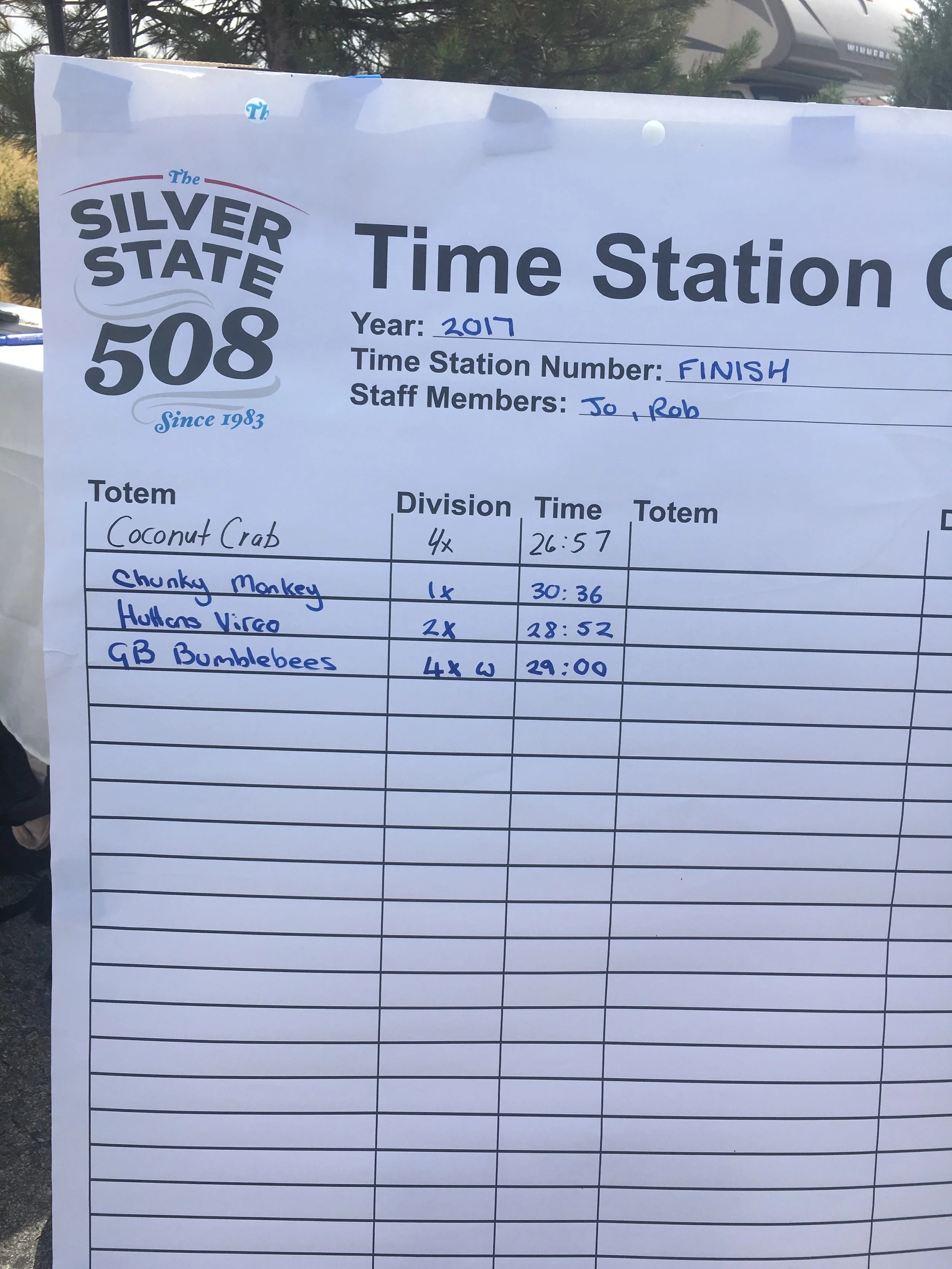

The run-down, in stage 3, was that we were well behind the four-man fast francophone team, Coconut Crab as well as the two-person mixed Hutton’s Vireo and, only recently, the other Reno/Great Basin Bicycles sponsored team, Great Basin Ichthyosaur. Their rider, Fritz, had passed Katie on Sand Pass, just after Sand Mountain. So, we were fourth or fifth (not including any solo riders)— and had something like twenty minutes before we expected Katie to ride by the van again. We all stood around, talking about Reno’s decision to close the strip clubs downtown and move them elsewhere. It was an odd conversation, admittedly, but I was wearing a tutu, we were driving in a mini-bus and there was something like 400 miles ahead of us. Who was I to judge what was strange?

Katie flew by historic Middlegate while both Great Basin teams "chillaxed" by the side of the road.

Linda, one of our crew, got out of the driver’s seat and located her yoga mat to do a series of therapeutic stretches and strengthening exercises. Seven weeks before, she was struck by an SUV in a four-way stop intersection in Carson City when the woman behind the wheel decided to put the pedal to the metal from a dead stop for no apparent reason. Linda’s pelvis was broken in multiple locations, and I was shocked when she told me she still wanted to crew for the team.

*

Carroll Summit is probably one of the most beautiful spots in Eastern Nevada. It’s technically not on “the loneliest highway” but a side road of that— on NV highway 722, a sharp right turn just after our semi-famous “shoe tree.” I had told Katie about the climb weeks before the race when she’d enthusiastically signed up for this epic adventure without asking me about it much (I worried about her sanity a little bit. :-) Actually, she saved our butts, and I’m glad she joined up with us.) Katie, who has competed in countless triathlons (mostly the long kind) had more aerobic base than all of us put together. But, TT bikes are built to do one thing (and they do it well): go fast on the flats and downhills.

Katie, climbing out of East Gate and up Carroll Summit.

Crew Linda Hayes pushed through considerable barriers to help us finish. I don't think I've ever met a stronger woman.

About a week before the race, I borrowed a friend’s TT bike and rode it around just to see what it felt like. It was like sitting on a tank— granted, it took some effort to get that thing going, but once I was rolling, I was unstoppable. Hills, though— yeesh— I’m typically a fairly decent climber, and I struggled on terrain I would, on my road bike, call “a hill.”

When we started the Carroll Summit climb, I changed out of my sweatpants and into shorts. Then, after stepping outside the mini-bus, I promptly put my pants back on again. Sharp rock formations frame the initial entrance to the canyon and an old farmstead called Eastgate, welcomes you to this new, strange world.

A fire swept over Carroll Summit last year, so the remains of juniper trees lend an eerie air to the otherwise stunning climb. Katie pushed through that climb like nobody’s business, but I can’t imagine what that was like on a TT bike. If determination were elements on the periodic table, Katie’s would be uranium.

Once the climb was over, she would reach over 50 mph on the downhill and pull us neck-and-neck with Reno’s third team: Blerch (a four-man team.) Great Basin Ichthyosaur had pulled 18 minutes ahead; Hutton Vireo 30 minutes and Coconut Crab, probably around an hour.

The last part of the stage is cruel: a sharp uphill and up-wind climb into Austin. I rolled around at the gas station on the hill to warm up. The rider on the Blerch team took a selfie with me at the exchange point. Then, as Katie came up the hill, I cheered her on while silently telling myself that it was time to saddle up and go into puke-mode for as long as I could stand it.

Stage 4: Almost getting run over, Austin to Eureka.

Up Austin Summit, I pass the other Reno team immediately. My legs are already filled with lactic acid, and I’m breathing so much cold air that it feels like I’m rubbing cheese graters up and down my throat. I can’t let my team down, and I know this stage well: as long as I don’t cross my own red line, I can make it on water and a few energy chews. It’s about 6:30 in the evening, the sun is low and the desert, beautiful. The low light captures the earth tone hues and distant, purple mountains.

I don’t expect to see my team vehicle for a while. And, that’s fine with me. I settle into a pace, down in my aerobars. Music— piano— plays in one ear while I listen to the endless wind— the sound of distance—around me.

Eventually, I do see the orange mini-bus. They offer me water. They offer me other things, but I don’t stop, can’t stop—it’s only 70 miles. I start in on the chews at thirty miles in. Grape flavored, I wonder why I didn’t check the package before I stuffed it into my pocket. But, as I’ve already said, I’m not really a details person, so whatever. Chews are chews.

The sun sets, and the sky turns rosy-violet-blue. My team tells me to turn my lights on. I do, stopping (only so briefly)— I’ve passed a lot of riders I don’t recognize, but not GB Ichthyosaur, and not the two-person mixed team from So. Cal. I keep pushing harder— or so I imagine— in this place of endless headwind and panoptic horizons that fade with the arrival of evening stars.

I move through every single emotion a person can as my legs turn around the crank of the bike. I’m great, I suck, I can ride forever, I need to stop, I’m powerful, I’m weak… the litany of narratives is endless and vast like the darkness and soon I can only see a single lighted spot on the road in front of me.

Riding into (or away) from the dusky, desert light. I put my head down and pushed as hard as I could, not stopping until my boyfriend made me crash because my lights went out and someone almost ran me over. I think I was second fastest on this stage out of every body.

Red blinking lights in the distance ahead tell me I’m catching riders, and I’m excited and I ride harder. Then, a white stalker-van pulls up next to me, and I turn to look and this man yells at me with big, gesturing arms. My heart is in my throat, and when I realize that it’s my boyfriend, Rich, and that he’s in his team van (GB Ichthyosaur) I’ve crashed my bike, bruised my arm, stomach and leg and I’m panting on the dark pavement.

He tells me my tail-light had failed and that some other motorist had almost killed me. He puts several lights on my bike, and pushes me back on the road. I’m less impacted by the news that I almost died than I am knowing their rider is close.

I catch her in the undulating terrain of 20-miles-to-go and call out a friendly greeting— the darkness is lonely. Up and down— I seek that other team, pushing as hard as I can. I tell my team to go to the exchange point even though I’m low on water. The final climb before Eureka, the horizon turns a light shade of lavender in the dark black of night. I pass a man on the climb to the gas station in town, and spot deer in between the old, brick buildings. I point, but the lights from the exchange points are so bright, they almost blind me.

I settle into the mini-bus. I remember we backed over a curb. I remember we followed Rhonda (who would ride the 70-mile stage 5) out of town. My body ached after that stage. I tried so hard, but I didn’t catch them all. I lay down onto a seat and tried to stop shivering.

Stage 5: Cold night and athlete-dreams, Eureka to Austin.

Taken through the front windshield (because everything was direct-follow at this point in the race) Rhonda braved the dark and cold. Admittedly, I slept through most of her leg, except for the moments she needed me.

As Rhonda set out on our return ride home, I scrambled to peel off the cold, wet layers of cycling clothes and settle into a seat to sleep, since I’d be the one to help our crew through the “deep” part of the night for the sixth stage of the race. A rider from another team drafted our mini-bus as we turned out of Eureka and back onto the lonely highway. I couldn’t get my teeth to stop chattering.

I felt bad for telling Rhonda (before the race) that it would not be a cold leg to ride. To my own credit, it wasn’t that cold the year I rode it— back in 2015, when I had competed on a two-person mixed team with Brandon Tinianov team Sanguine Octopus (we captured the course record that year following the race results that include stopping at every stop sign and riding each and every leg to which we were assigned without changing out riders—which, for this race, constitutes cheating.)

Rhonda kicking ass up Geiger like she did up Austin Summit. The temps dropped below freezing. Her fist-pump at the summit was the most inspiring moment of the race.

Taken from her first stage, Rhonda probably rode the second one just like this. She would complete the stage as the second fastest rider regardless of gender.

This year, it wasn’t just cold. It was— just about, literally— freezing. I couldn’t warm up in the bus; I couldn’t imagine what that felt like in the dark night at 20+ mph. Linda drove the mini-bus, directly following Rhonda (per the race rules).

The other rider— a man on a four-person team— surged in front of Rhonda and the bus, only to drop back, and have us overcome her. This happened about three times before he shook his head and silently accepted that “the girl team” would move ahead of him.

I kept trying to sleep. I listened to my teammate, Katie— who is a seasoned triathlete— talk to Linda about her ultra-triathlon experiences. As they talked about the swim-bike-run, my dreams turned triathlon: I swam through deserts. I biked across a pool. It was really, really weird.

Then, at some point, I heard my name and bolted awake. Rhonda’s headlight had failed. Without thinking, I ran to the bike rack on the back of the bus where the rest of our bikes rested. I loosened the headlamp on my bike and ran to Rhonda, attempting to fasten it to her handlebars. Immediately, my fingers were almost too cold to move, and it took me three or four attempts to get the light secured on her bike.

I’m still upset with myself that I didn’t capture any pictures of Rhonda riding this leg. I was so tired and cold, and I knew that my shift of co-piloting would start in Austin. Rhonda rode it brilliantly— she was second fastest time overall on that leg of the race out of 46 teams. She was barely behind the four-man French team Coconut Crab, and decimated everyone else in the race.

I remember, back in 2015, climbing the last climb, Austin Summit. It’s brutal: it is dark, you can’t see where you are going or how far you have come. The year I did it, I glanced into the night sky and happened to see a shooting star. I wished that the climb would end. Then, out of the darkness, the green highway sign announcing Austin materialized. I held my arms in the air.

I was awake for Rhonda’s final climb. I watched as she passed other riders. I watched as she pushed hard up that final ascent, not being able to see it. And then, as the sign came into view, she lifted a single fist-punch into the air: the sign of victory. It was one of the most inspiring moments of the race.

Stage 6: Deep freeze, dark morning and mysteries.

We arrived in Austin at 1:32 am. It was dark and Pluto-cold; I’m honestly surprised there was no trace of ice on the roads. My teammate, Monica (who would ride the 112 mile stage from Austin to Fallon) was, due to her extensive experience as an athlete, ready to ride. When we arrived in Austin earlier (when I began Leg 4), she and her boyfriend left the orange bus, and rented a room in Austin. They had a warm meal, showered and slept while Rhonda and I rode to Eureka and back again.

This picture is taken much later, after dawn (obviously.) Here, Monica is cruising through the Salt Flats like nobody's business. This woman rocks.

There was nothing in the race rules which stated all riders must remain in their vehicle, or that they cannot rent rooms in the tiny towns we would pass through. In fact, we were encouraged to support these small economies as much as we could. So, Monica did her part and ate at one of Austin’s two restaurants and stayed in one of its three motels.

When we arrived in Austin, I grabbed Rhonda’s bike, put it on the bike rack and ushered her into the bus. I checked with Monica to see that she was ready. Her boyfriend, Matt, took over the job of driving as crew while Linda (still recovering from a major injury) would sleep and shower in their hotel room and drive his car to Fallon where we would meet, switch drivers, and continue to the finish line.

Matt, a high school government teacher in Reno, took the wheel. A true adventurer and athlete, I did my best to support our team even though late-night anything is really not my strong suit. We made sure Monica turned left onto highway 722 (a turn other riders missed); we made sure she had water and food.

Yet, he said that more than a few times, I would be talking to him and mid-sentence, would fall completely asleep. (Honestly, I tried.)

Every time I heard my name, I jumped to action: I filled a water bottle, I fixed a headlight, I gave or removed gloves.

Monica flew. The team in front of us— a two-mixed team— had a fifteen minute lead on us leaving the Austin time station. I watched the online tracking on my phone and the blinking red lights in front of us simultaneously: she was gaining on them, and gaining fast.

I know Monica saw the blinking tail lights: Matt said that she would do everything to catch them. She is tenacious like that. We reached the bottom of Carroll Summit and gave her a new warm layer (that she could sweat in) new water (hers had frozen due to riding in 19-degree temps and a handful of encouraging words. The red flashing lights became more brilliant as we approached.

And then, the lights vanished.

I can’t say what happened. Wake and slumber flatlined, and even after reviewing race data, I cannot tell the true story. Yet, after a month of reflection, I have this unframed thought: that for all the hours and all the discomfort, athletes are left only one thing to celebrate— integrity. At our best, we represent this particular strength of spirit through the extremes we push the body by completing feats most people would rather not even try. We are integrity, embodied.

If determination was personified, it would be Monica. Pictured riding through the salt flats at dawn after nearly 80 miles of riding through dark and cold and absolute. Honored to call her my teammate and friend.

Yet, without integrity— when the rules aren’t followed, and when excellence is arrived at by cheating, there is nothing to frame: an athlete is just another person who would rather not complete a difficult race.

I can say that Monica rode 112 miles (fast!) for that stage of the race. I watched her do it. I was awake for every stop and, when Matt had a question, he would wake me up to ask.

Dawn across the alkali flats, dawn over Sand Mountain: Monica rode steady and strong. When we stopped at a gas station at the outskirts of town, we heard the Fallon Naval Base play the Star Spangled Banner. Delirious from lack of sleep, we stumbled out of the bus, placed our right hands over our heart, and stared up at the American flag flying over the gas station. The gas station owner—and his wife— joined us.

Stage 7: Time Trial: It’s getting real.

Monica and Katie made the exchange while I was putting my cycling clothes on in the orange bus. I had made another dry sandwich of turkey and white bread (because that was all I had to eat) and another bottle of water. Monica asked if we wanted coffee drinks while Rhonda and Katie found a local cafe in Fallon for breakfast and real coffee.

Katie seriously flew on her final stage into Silver Springs.

Katie pushed so hard for this race, and as her first cycling-specific event, she really threw down a strong performance.

My stomach was in knots: I tried to do my best with what I had. Katie leaves the exchange point on the Q-Roo TT bike, flying fast down the flat terrain. We gather Monica in the bus and continue to the turn. Everyone but Katie and I are eating non-bike food and relaxed. My nerves are sharp and when Rhonda asks me what I know about other riders in the ride (and what to do when they don’t follow the rules) I don’t have an answer for her.) There are rules and relationships: you should always follow the race rules. I don't have an answer for her about the other half of it, relationships, the nebulous part.

As the morning warms, I worry that I’ve let everyone down. Katie rides so strong; she is steady and strong due to her large-volume training and grit. When we pull into Silver Springs— a casino parking lot as the exchange point— I go into the bathroom one last time before my ride.

In the casino bathroom, I look at myself in the mirror. My face looks completely horrible. I’m wrinkled, tired and old. While Katie kicks ass on her final stage of the race, I take boogers out of my eyes and ears, and put the mass of my hair into a ponytail.

As I leave the cigarette-scented environment in the casino, guilt seeps from my blood into every part of my body.

Stage 8: Making up (stolen) time

When Katie and I make the exchange, there is not another team around us. It’s just desert and distance. Former Race Director and always-race-guru/photographer, explorer/instigator Chris Kostman filmed me riding for a time in his car along highway 50, even taking his blue Saturn off onto the dirt shoulder of the road. Kostman, a friend and supporter of my writing, kindly offered his thoughts on our bumblebee team: “It was a true pleasure to have our first four women team on the Silver State 508 course!” No pressure, right?

A beautiful morning for a bike ride, even if I was a little sore. Photo credit: Chris Kostman

No matter what I tried to tell myself, my muscles— and body— were not 100% due to how hard I’d pushed in the fourth stage and probably my lack of sleep since then. I felt mechanical— and half-alive— as I turned my pedals around the crank. I worry someone might catch me, but there is nothing in the world that tells me that there is another person around me.

Pushing up the first part of Six Mile Canyon. I felt like I was riding so slowly.

At some point, a truck carrying bottled water had a wreck and I had to negotiate broken plastic bottles across the highway. Then, when I turned onto the road leading to the climb up Six Mile Canyon, I encountered an older man on a bike. He asked me if I did the Alta Alpina races to which I answered that I had.

My team, who drove up shortly after this exchange, were alarmed by this early Saturday morning rider who, they said: “was all over the place.” Afraid he was going to weave into me and force a crash, they told him to back off, which he eventually did, as I attempted to hold a steady pace and cadence up the pitchy and sometimes-steep climb of Six Mile Canyon.

Another shot as I climb Six Mile Canyon.

I’m not going to lie— I felt like I was riding in slow motion, and I figured that I had no shot at catching anybody. I felt bad for my team— whom I’d dragged out into the desert for a night of no-sleep, below freezing temps, mediocre food, and the opportunity to water a lot of bushes along the way. I knew they deserved more out of me, and I was sad that, in the terrain where Rich says I shine, I was barely making it.

I didn’t have any idea where George was, and I told myself to just ride my ride. So, I listened to the piano chords in my right ear and fell into the rhythm of the road, pushing the steeper sections and easing up on the flats to give myself a slight recovery. I would only find out later, after the race had ended, that I was catching the war-torn rider ahead who went to considerable extremes to keep me from catching him.

Down Geiger Grade, I held onto my aerobars, not touching the brakes once. Unfortunately, I caught just about every light red on the way back. And, wanting to adhere to race rules, I stopped for each of them. I came into the finish line hot, though, and I think there was genuine concern that I would crash out on that final turn. But, I owe whatever I know of the bike to Rich Staley who’s taught me how to ride hard, turn on a dime go back to the barn soaking wet with sweat, dirt and tears— and to make sure that everyone else on the course suffered more than I did. I would ride the fastest final leg, out pacing the next rider by about ten minutes. I nearly did catch that guy in front of me. His twenty minute lead dwindled to eight minutes by the time I crossed the line.

A part of me wonders if I would have caught him had my luck been better, RE: the traffic lights. Rules are rules, however, and everyone who competes in this race is a warrior in one way or another.

Skidding into the finish line. Rich Staley taught me how to finish in style!

Finish Line.

Our team would come in third overall— impressive for the Silver State’s first all-female team comprised of my friends… other women who embody what this sport is all about: bravery, honor, integrity and grit.

Kostman, when we crossed the line, would say: “Team Great Basin Bumblebee not only burned up the course, but they did it with style and with great smiles, strength and poise, no matter the conditions.”

Wearing our jerseys, team Great Basin Bumblebee showed the world that women can work together, women can compete, women can be strong, and women can win!

Group hug with long-time race director, adventurer and guru Chris Kostman.

Thirty minutes later, the other Great Basin Team, Ichthyosaur, would cross the finish line, too. “It’s also exciting to have so many locals embracing the race, and I’m sure these talented, energetic ladies will inspire others,” Kostman said.

After taking each team’s finishing photo, we gathered for a group hug that included both Great Basin teams and Chris Kostman. It was truly an incredible moment for all of us.

Officially, we would finish 3rd of all teams that competed in the Silver State 508 this year. We would also capture the course record for an all-woman four-person team. No other four-woman team competed in the race this year; and only a handful have ever completed this race.

For races like the Silver State 508, you don’t come away with much— a few saddle sores, dirty cycling clothes and a jersey. Added all together, it’s probably a net loss of resources, but what you gain from the experience— and the challenge— is priceless. For me, I found something unexpected in the desert this year. As our team packed up our individual items, cleaning out the orange bus and saying our goodbyes, I knew I was going to miss these remarkable women who shared the toughest 48 hours of sport with me.

For all the animosity competition can bring, this race reinforced the incredible capacity of the human spirit to reach for— and exceed— its own greatness. Granted, I wasn’t ready to start talking about our plans for next year (I needed a shower first); but events like the Silver State 508 bring out the best— and worst—in each of us. Not giving up, pushing through discomfort and supporting our riders and other teams— these are the memories that surface when I think back to this race.

That, and the incredible way we kicked nearly everybody’s ass.